The History and Legend of Santa Claus Uncovered

Santa Claus is a global icon. Everyone knows Santa Claus, but only a few know much about his origins. It's an exciting story that crosses ages and countries and dates long ago.

The Story of Santa Claus: The Origin and History of a Christmas Legend

Santa Claus, also known as Saint Nicholas or Kris Kringle, has a long history steeped in Christmas traditions.

We take Santa for granted these days. Today, everyone thinks of Santa Claus as the jolly man in red who brings toys to good girls and boys on Christmas Eve, but his story stretches back to the 3rd century. Where did this friendly old man in a red suit come from who brings gifts for children? So, if you're keen to know where the man in red came from and his story, you jumped on the right article.

Here it is, finally, the most complete story of Santa Claus.

Santa Claus, also known as Saint Nicholas or Kris Kringle, has a long history steeped in Christmas traditions. Around the world, there are different versions of the jolly, bearded man who delivers gifts to children in December or, in some countries, January.

However, as we know him today, Santa Claus only arrived in 1822.

We take Santa for granted these days — every Christmas, blizzard or not, he presents to all the world's believers, delivering toys and candies to good kids all around the globe. However, Santa Claus has not always been the jolly man in red we know today. And his suit is not always red in all countries worldwide. For example, his suit is blue in certain nations instead of the most common red one. And strange as it may seem, Santa Claus has been banned from the country for some time. More about this in one of the paragraphs in this article.

Please keep reading if you want to know more about the true origins of Santa Claus.

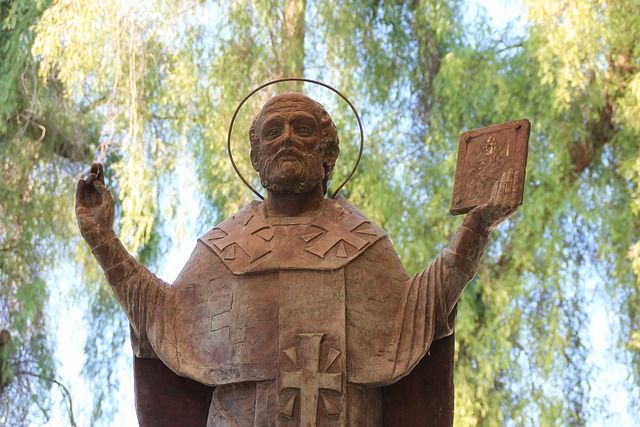

Saint Nicholas, the 'original' Santa Claus

The origin of Santa Claus can be traced back hundreds of years to a monk named St. Nicholas.

Around 270 A.D., a man called Nicholas was born in Lycia, in what is now Turkey. According to NBC News, Nicholas became a bishop as a young man. Always compassionate and keen to help the less fortunate, he became known for paying the dowries of girls from low-income families to prevent these unfortunate girls from being forced into slavery or prostitution (which is, indeed, a form of slavery.) In the better-known tale, three young girls are saved from a life of prostitution when young Bishop Nicholas secretly delivers three bags of gold to their indebted father, which will be used for their dowries, thus saving the girls from living a horrible life.

Nicholas was also known for leaving coins or other treats in the shoes of local children, and eventually, the little punks started the habit of leaving their shoes out on purpose in the hope of finding something good inside them the next day.

In traditional images, Nicholas is usually portrayed wearing a red cloak, much like our modern Santa. However, he is also said to have had a small orphan boy working as his helper, which we now consider Santa's first elf.

Nicholas died on December 6 and was canonized shortly after that as the patron saint of children. After his death, people honored him with a December 6 feast each year and carried on the tradition of leaving gifts in children's shoes. We can think of this as the first manifestation of an 'early' Santa Claus. At some point, St. Nicholas was the most popular saint in Europe. His remains are supposed to be in the Basilica of Saint Nicholas in Bari, Italy, built in the 11th century. Many believe it houses the mortal remains and holy relics of St. Nicholas. Even after the Protestant Reformation, when the veneration of saints began to be discouraged, St. Nicholas maintained a positive reputation, especially in Holland.

Image by Rigo Neumann from Pixabay

Sinterklaas

For a while, St. Nicholas became mainly a Dutch thing. Protestantism frowned upon the celebration of saints as a form of idolatry. Hence, parents had to tell their kids that not only was St. Nicholas forbidden, but they wouldn't be getting any presents on December 6.

After St. Nicholas got the Protestant ban, people mostly stopped celebrating December 6, except in the Netherlands, which went on with the feasting and the gift-giving anyway.

According to Business Insider, the Dutch called Nicholas "Sinterklaas," a shortened form of Sint Nikolaas (Dutch for Saint Nicholas). Sinterklaas was the rough outline of our modern Santa — not only did he do the whole leaving-gifts-in-shoes thing, but he also wore the red bishop's robes of the original St. Nick. Elves assisted him in the Middle Ages, and he developed that incredible magic of Santa that got him out of chimneys. Although he hadn't yet discovered flying reindeer, he did seem to have at least one flying horse. Incidentally, to get a gift, you were expected to leave some treats out for the horse, which explains why Sinterklaas hadn't yet reached traditional Santa Claus rotundity. (Cookies would come in later centuries.)

Father Christmas and the German gift-givers

Other European cultures maintained some form of St. Nicholas, too — in Britain, he was known as "Father Christmas," He wandered around town and invited himself to random houses for Christmas dinner.

And there were also the German gift-givers, who were a clever way of skirting the Protestant moratorium on St. Nicholas. According to National Geographic, the Germans moved the gift-giving day to Christmas. However, some of these scary Germanic figures again were based on Nicholas, no longer as a saint but as a threatening sidekick like Ru-Klaus (Rough Nicholas), Aschenklas (Ashy Nicholas), and Pelznickel (Furry Nicholas). These figures expected good behavior or forced children to suffer consequences like whippings or kidnappings. And so, on the one hand, the German gift-givers brought gifts. But, on the other hand, they also whipped naughty kids, which made them a much less reassuring version of the 'modern' Santa we know today.

Santa has Norse genetics.

Long before the Germans, the Norse had their own creepy story of a terrifying gift-giver who would appear during the winter festival. According to the Norwegian American, on the night of the winter solstice, the God Odin would fly around on an eight-legged horse, terrorizing anyone unfortunate enough to be out after dark.

Odin might also turn into smoke and come down the chimney, which is obnoxiously creepy. Still, kids would leave their boots next to the fire and then cower in excited anticipation. Odin would fill their boots with candy and toys if he felt generous.

Early stories and poems

In the early 1890s, the Salvation Army needed to raise money to pay for the free Christmas meals they provided to needy families. So they began dressing up unemployed men in Santa Claus suits and sending them into the streets of New York to solicit donations. Those familiar Salvation Army Santas have been ringing bells on the street corners of American cities ever since.

Once in America, all these different versions of Saint Nicholas mingled and popularized until one day in 1809 when Washington Irving decided to put a sort of merged version of them into a book called Knickerbocker's History of New York. The story was the first to portray St. Nicholas in a flying wagon, delivering presents only to well-behaved kids.

A few years after the History of New York, The Saint Nicholas Center tells us that an anonymous author published an illustrated poem called "The Children's Friend," which gave St. Nicholas a new name: Sante Claus. In this portrayal, Sante Claus came from the north in a sled pulled by a single reindeer and arrived on Christmas Eve.

The Night Before Christmas

Image by Kevin Sanderson from Pixabay

Santa Claus as we know him arrived in 1822, a fully fleshed-out amalgamation of St. Nicholas, Sinterklaas, Odin, Father Christmas, and Sante Claus. In 1822, Clement Clarke Moore, an Episcopal minister, wrote a long Christmas poem for his three daughters entitled "An Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas," more popularly known as "'Twas The Night Before Christmas."

In "Twas The Night Before Christmas," which is still a traditional Christmas Eve read for families worldwide, Santa is portrayed as a "right jolly old elf" who arrives in a flying sled pulled by not one but eight reindeer. Some of Moore's imagery was probably borrowed from other sources. However, his poem helped popularize the now-familiar image of Santa Claus, who flies from house to house on Christmas Eve in an eight-flying reindeer"miniature sleigh" to leave presents for deserving children. At this point, Santa Claus almost looked as we know him today.

Stalin banned Santa Claus in Russia.

The Russian Santa is called Ded Moroz, which roughly translates to Grandfather Frost. Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) is slender with a wizard-like flowing beard, and he wears a long robe that comes in different colors, such as blue and white. He is assisted not by elves but by his beautiful granddaughter, Snegurochka (Snow Maiden). His sleigh is powered not by reindeer but by three steely horses.

But what sets Russia's Santa Claus apart from his Western counterpart is the turbulent century he's faced. Like the Puritans, the Bolsheviks initially opposed the Russians' Christmas-like New Year's celebration, including its fir tree and gift-bearing old man. As Karen Petrone explains in Life Has Become More Joyous, Comrades, the holiday was considered "bourgeois," and Ded Moroz was banned in 1928, having been "unmasked as an ally of the priest and the kulak.". Nevertheless, he has survived a violent social and political revolution that saw him go from being beloved to being banned as a subversive element, then beloved again, and eventually hailed as a symbol of the true Russian spirit.

By the 1930s, Joseph Stalin was starting to get what his people wanted. They wanted Ded Moroz and his traditions back.

So finally, in 1937, Ded Moroz returned to Russia, with Joseph Stalin ordering him to wear a blue cloak so he wouldn't be confused with the American capitalist Santa Claus.

"In Soviet usage, [Ded Moroz] is presented as a good spirit who inspires hard work in Soviet children," The Virginia Advocate explained on December 22, 1949. So he brought back holiday gift giving, but at New Year instead of Christmas. That was okay, apparently, because New Year was a secular holiday and therefore magical, gift-bringing elves could show up as long as they didn't have anything to do with the Western world. Stalin even put Father Frost in a blue coat instead of a red one, so no one would confuse him with Santa, who was totally different even though the two traditions were pretty much the same.

Santa didn't have a wife until 1849

The original Saint Nicholas didn't have a wife because bishops mostly didn't do that in the fourth century A.D. Still, Santa remained mysteriously unwed until the middle of the 19th century.

Despite all the apparent lifestyle barriers between Santa and anyone he wanted to ask out, in 1849, the first reference to a Mrs. Claus finally appeared in a short story entitled "A Christmas Legend," featuring a young couple disguised themselves as Mr. and Mrs. Claus. That was evidently enough to get the snowball rolling, and today Mrs. Claus appears in many popular stories.

Santa's Suit and the North Pole

Most of the Santa Claus incarnations have worn some version of the red suit he wears today, from a long bishop's robe to a fur-trimmed coat. But at some point, Santa's garb became standardized, primarily thanks to the popularity of printed magazines like Harper's Weekly.

According to History, in 1881, cartoonist Thomas Nast drew an image of Saint Nicholas based on his description in "Twas The Night Before Christmas." Nast's drawings included the fur-trimmed suit, thick white beard, and plump belly we know today, along with one of the first images of Mrs. Claus.

Incidentally, Nast was also responsible for popularizing the idea of a Santa-led North Pole workshop. It's pretty easy to see why — the North Pole was always cold and snowy, and Christmas was associated with cold, snowy temperatures. The North Pole was also romanticized since it was remote and unspoiled. So it was the most logical place for everyone to imagine the perfect location for Santa's giant workshop full of elves.

Thanks, Coca-Cola

It's worth remembering that part of our culture has been shaped by advertising. Even some of our beloved traditions would not exist in their current incarnations if multimillion-dollar companies did not deem it so.

According to Business Insider, in the 1920s, Coca-Cola was feeling annoyed because no one thought that an ice-cold Coke sounded good in subzero temperatures. So instead of inventing a hot version of Coca-Cola (and we are thankful they didn't), they started aggressively marketing Coke as something you could enjoy during the holidays. First, they hired an illustrator to create a Santa Claus with a cheerful face and a lovable demeanor.

The cheerful, friendly version of Santa persisted, and that's mostly how we still imagine him today.

The real face of Santa revealed

Everyone was happy with the idea of a friendly, slightly oversized, and always-smiling Santa Claus. However, researchers couldn't leave well without certainties about the 'real' Santa Claus' appearance. So, in the 1950s, someone decided to dig up the bones of the real St. Nicholas, and then in 2014, researchers used the measurements of his skull to reconstruct his face forensically.

Researchers painstakingly reconstructed St. Nicholas's face and discovered that he'd looked exactly like he did in his ancient portraits and less like his modern Coca-Cola ones.

Does Santa only use sleds to deliver gifts to children?

Santa Claus's favorite mode of transportation is the sled, which is handy for getting him out of the ice-clogged North Pole. But only some places on Earth are blanketed with snow during the holidays. In Australia, for example, Christmas is a summer holiday, and a reindeer-pulled sled wouldn't be convenient.

As it turns out, Santa often trades in his sled for a different mode of transportation during his Christmas Eve journey. According to the Huffington Post, Santa Claus is called Sinterklaas in the Netherlands. He doesn't live at the North Pole, but in sunny Spain and arrives by steamboat with a helper called Black Peter rather than an elf. In Australia, he trades the reindeer for white kangaroos, also called "boomers." In France, he's called Pere Noel, and he shows up riding a donkey named Gui.

Whatever the tradition, Santa is still pretty much Santa. And is, and will always be, magic. Regardless of what he looks like, what mode of transportation he uses, or how fat and jolly he is, the legend of Santa is still magic for millions of kids, with an extraordinary history that makes his tradition especially sweet.

Article references: Grunge.com

and Santa Claus: Real Origins & Legend

and Time